Avon Park, Florida

Avon Park, Florida | |

|---|---|

| City of Avon Park | |

| Nickname: The City of Charm | |

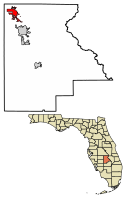

Location of Avon Park in Highlands County, Florida. | |

| Coordinates: 27°35′40″N 81°30′12″W / 27.59444°N 81.50333°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Highlands |

| Settled | 1884 |

| Incorporated (Town of Lake Forest) | 1886 |

| Incorporated (City of Avon Park) | January 1, 1926 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Garrett Anderson |

| • Deputy Mayor | Jim Barnard |

| • Councilmembers | Brittany McGuire, Michelle Mercure, and Berniece Taylor |

| • City Manager | Danielle Kelly |

| • City Clerk | Christian Hardman |

| Area | |

• Total | 10.45 sq mi (27.06 km2) |

| • Land | 10.13 sq mi (26.24 km2) |

| • Water | 0.32 sq mi (0.82 km2) 12.4% |

| Elevation | 121 ft (37 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 9,658 |

| • Density | 953.31/sq mi (368.08/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 33825-33826 |

| Area code | 863 |

| FIPS code | 12-02750[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0278007[4] |

| Website | www |

Avon Park is a city in Highlands County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 9,658, up from 8,836 at the 2010 census[5] but down from the 2018 estimated population of 10,695.[6] It is part of the Sebring, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area. It is the oldest city in Highlands County, and was named after Stratford-upon-Avon, England.

History

[edit]The first permanent white settler in Avon Park was Oliver Martin Crosby, a Connecticut native who moved to the area in 1884 to study the wildlife of the Everglades. By 1886, enough people had followed that the "Town of Lake Forest" was founded. As president of the Florida Development Company, he recruited settlers to the area, many of whom were from England, including many from the town of Stratford-upon-Avon, who gave the town its name.[7]

1927–29 spring training ground of the St. Louis Cardinals

[edit]From 1927 to 1929, Avon Park's newly constructed Cardinal Field (now Head Field) was the spring training ground of the St. Louis Cardinals, a Major League Baseball team. Avon Park resident Charles R. Head convinced his friend Sam Breadon, the owner of the Cardinals, to move the baseball team's spring training ground to the city.

The spring training matches were very popular affairs and many matches saw attendances above the entire population of the city. On March 16, 1928, before a spring training match between the New York Yankees and St. Louis Cardinals, residents presented Yankees player Babe Ruth with a 52 in (130 cm), 14 lb (6.4 kg) commemorative baseball bat in a pre-game ceremony. Ruth also struck a home run which landed on a nearby street and the city had the street renamed "Ruth Street" in his honor.

At the end of the agreement in 1929, Breadon moved the Cardinals' spring training ground to Bradenton, citing inadequate hotel facilities and poor field conditions. Avon Park mayor C. S. Donaldson disputed Breadon's accusations and claimed that the city had five excellent hotels and that the field was well maintained, had a modern clubhouse to accommodate players, and was even built to the specifications of the team, under the supervision of a Cardinals groundskeeper.[8][9]

Gough v. State

[edit]In September 1949, the city elected the youngest mayor in United States history at the time, 21-year-old Wiley Sauls Jr., largely due to the votes of the second precinct, which was populated mostly by black residents. Sauls Jr. received 76% of the precinct's votes, and he went from third out of five candidates to first and usurped incumbent mayor O. C. Wilkes, who only received 20 votes from the second precinct.

In the following city-wide election on September 11, 1951, the second precinct was allowed for the first time to be staffed and managed by its majority black populace. The overseeing inspector of the second precinct and the second precinct's clerks were all black. Wilkes challenged Sauls Jr. for the mayorship, and he received a slim eight vote majority in the first precinct, but Sauls Jr. received 92.5% of the votes in the second precinct and comfortably defeated Wilkes. Two new city councilmen, Mannin Kirkland and J. B. Sparks, were also elected to the city council largely due to the votes of the second precinct.

The incumbent city council met four days after the election and heard Wilkes' protest, who claimed that there were voter irregularities in the second precinct and that they should install him as mayor. The city council refused Wilkes' demands, but he began lobbying local influencers and convinced the council to convene a special session on September 25. Wilkes alleged in this second meeting that the second precinct had not returned all of its blank ballots after the election and that this called into question the validity of the results. The council voted 3–1, with one abstention, to throw out the votes of the second precinct, which prompted Wilkes to immediately begin acting as mayor, while Kirkland and Sparks were to be replaced by E. W. Gough and Oscar Wolff.

Sauls Jr., Kirkland, and Sparks hired attorney Keith Collyer, who argued that it was unlawful that a mere claim of irregularities would give the council the authority to install themselves into office in the face of a challenge to their power. While the circuit court sided with Sauls Jr., Kirkland, and Sparks, and demanded that the three be put into power, Wilkes and the council through attorney S. C. Pardee Sr. pushed the case upwards through the judicial system and also began to argue that the second precinct's inspector, W. J. Robinson, had helped people to cast their ballots. The Supreme Court of Florida also voted in favor of Sauls Jr., Kirkland, and Sparks, and the three were then installed as mayor and councilmen respectively and put municipal governments on notice that they did not have the authority to invalidate an election in order to remain in power.[10][11][12]

1950s military plane crashes

[edit]On November 4, 1950, a Republic F-84 Thunderjet being flown by 22-year-old Donald Floyd Whiston of the United States Air Force from Naval Air Station Albany (formerly Turner Air Force Base) during training for the Korean War, crashed into the ground, killing Whiston, at the Avon Park Air Force Range, just northeast of the city, after apparently stalling in the sky.[13][14]

Less than eight years later, on March 21, 1958, a Boeing B-47 Stratojet being flown from MacDill Air Force Base crashed into the ground at Avon Park Air Force Range. All four occupants were killed in the resulting explosion.[15]

Operation Drop Kick

[edit]In 1956, the U.S. Army Chemical Corps released 600,000 uninfected yellow fever mosquitoes from a plane from Avon Park Air Force Range over the city in order to test how efficiently the mosquitoes spread after conducting a similar experiment in Savannah, Georgia earlier in the year. The experiment was part of Operation Drop Kick, a series of military experiments to determine the practicality of employing mosquitoes to carry an entomological warfare agent in different ways. A day after the release the mosquitoes had spread between 1 mi (1.6 km) to 2 mi (3.2 km) in each direction and bitten many residents.

In 1958, the Chemical Corps conducted further tests from Avon Park Air Force Range and determined that mosquitoes could be easily disseminated from helicopters, devices dropped from planes, or by being deployed from the ground. Chemical Corps researchers found that the mosquitoes would spread more than a mile in each direction from where they were deployed and that they would quickly enter all types of buildings.[16]

On October 28, 1980, the documents detailing the experiments were declassified as part of the Church of Scientology's legal battles with the federal government under the Freedom of Information Act. After the Church of Scientology obtained the documents, the group made them available to journalists.[17]

2006 Illegal Immigrant Relief Act

[edit]In 2006, then mayor Thomas Macklin proposed City Ordinance 08-06, or the Illegal Immigrant Relief Act, which would have blocked the issuance or renewal of city licenses to businesses that hired undocumented aliens, fined any property owner who rented and leased property to undocumented aliens, and established English as the city's official language, banning the use of other languages during the conduct of official business except where specified under state or federal law.[18] In the weeks before the vote, local businesses saw a drop in sales as immigrants became wary of coming into shop and droves of workers stopped showing up to local farms out of fear of being arrested.[19] The ordinance was defeated by the city council, on a 3–2 vote.[20]

Geography

[edit]Avon Park is located in northwestern Highlands County at 27°35′40″N 81°30′12″W / 27.59444°N 81.50333°W (27.594418, –81.503437).[21] 27/98 is the main highway through the city, leading north 23 miles (37 km) to Lake Wales and south 10 miles (16 km) to Sebring. Florida State Road 17 (Main Street) leads east through the center of Avon Park, then south 10 miles to the center of Sebring. Florida State Road 64 leads west from Avon Park 19 miles (31 km) to Zolfo Springs.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Avon Park has a total area of 8.2 square miles (21.2 km2), of which 7.1 square miles (18.5 km2) are land and 1.0 square mile (2.6 km2), or 12.43%, are water.

The city is located in a karst landscape underlain by the limestone Florida Platform, and numerous circular lakes are either within the city limits (Lake Tulane, Lake Verona, and Lake Isis) or border the city (Lake Anoka, Lake Lelia, Lake Glenada, Lake Lotela, Lake Denton, Little Red Water Lake, Pioneer Lake, Lake Brentwood, Lake Byrd, Lake Damon, and Lake Lillian).[22]

Climate

[edit]The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and warm winters. According to the Köppen climate classification system, Avon Park has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa).

| Climate data for Avon Park, Florida, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–2022 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

93 (34) |

92 (33) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 84.1 (28.9) |

85.8 (29.9) |

88.4 (31.3) |

91.6 (33.1) |

94.9 (34.9) |

96.4 (35.8) |

96.1 (35.6) |

96.0 (35.6) |

94.5 (34.7) |

91.2 (32.9) |

87.6 (30.9) |

85.0 (29.4) |

97.6 (36.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 73.0 (22.8) |

76.4 (24.7) |

80.0 (26.7) |

84.7 (29.3) |

89.4 (31.9) |

91.4 (33.0) |

91.8 (33.2) |

92.3 (33.5) |

90.2 (32.3) |

86.1 (30.1) |

79.7 (26.5) |

75.4 (24.1) |

84.2 (29.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 61.1 (16.2) |

64.2 (17.9) |

67.7 (19.8) |

72.6 (22.6) |

77.8 (25.4) |

81.3 (27.4) |

82.4 (28.0) |

82.8 (28.2) |

81.2 (27.3) |

76.1 (24.5) |

68.9 (20.5) |

64.2 (17.9) |

73.4 (23.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 49.2 (9.6) |

52.0 (11.1) |

55.4 (13.0) |

60.5 (15.8) |

66.1 (18.9) |

71.3 (21.8) |

73.0 (22.8) |

73.3 (22.9) |

72.3 (22.4) |

66.2 (19.0) |

58.1 (14.5) |

53.0 (11.7) |

62.5 (16.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 31.1 (−0.5) |

34.7 (1.5) |

39.4 (4.1) |

46.4 (8.0) |

55.8 (13.2) |

66.2 (19.0) |

68.9 (20.5) |

69.0 (20.6) |

66.1 (18.9) |

51.3 (10.7) |

42.8 (6.0) |

35.5 (1.9) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

23 (−5) |

34 (1) |

44 (7) |

51 (11) |

60 (16) |

61 (16) |

58 (14) |

38 (3) |

29 (−2) |

20 (−7) |

18 (−8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.42 (61) |

2.01 (51) |

2.61 (66) |

2.63 (67) |

3.86 (98) |

9.24 (235) |

7.41 (188) |

7.56 (192) |

7.45 (189) |

3.26 (83) |

2.16 (55) |

2.07 (53) |

52.68 (1,338) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 14.6 | 16.3 | 15.7 | 13.8 | 7.8 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 109.9 |

| Source: NOAA[23][24] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 890 | — | |

| 1930 | 3,355 | 277.0% | |

| 1940 | 3,125 | −6.9% | |

| 1950 | 4,612 | 47.6% | |

| 1960 | 6,073 | 31.7% | |

| 1970 | 6,712 | 10.5% | |

| 1980 | 8,026 | 19.6% | |

| 1990 | 8,042 | 0.2% | |

| 2000 | 8,542 | 6.2% | |

| 2010 | 8,836 | 3.4% | |

| 2020 | 9,658 | 9.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] | |||

2010 and 2020 census

[edit]| Race | Pop 2010[26] | Pop 2020[27] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 3,647 | 3,933 | 41.27% | 40.72% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 2,363 | 2,544 | 26.74% | 26.34% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 20 | 25 | 0.23% | 0.26% |

| Asian (NH) | 70 | 55 | 0.79% | 0.57% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 1 | 4 | 0.01% | 0.04% |

| Some other race (NH) | 21 | 17 | 0.24% | 0.18% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 138 | 267 | 1.56% | 2.76% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 2,576 | 2,813 | 29.15% | 29.13% |

| Total | 8,836 | 9,658 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 9,658 people, 3,787 households, and 2,420 families residing in the city.[28]

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 8,836 people, 3,146 households, and 2,146 families residing in the city.[29]

2000 census

[edit]At the 2000 census,[3] there were 8,542 people, 3,218 households and 2,114 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,841.8 inhabitants per square mile (711.1/km2). There were 3,916 housing units at an average density of 844.4 per square mile (326.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 58.90% White, 29.2% African American, 0.32% Native American, 0.69% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 8.35% from other races, and 2.28% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 18.71% of the population.

In 2000, there were 3,218 households, of which 28.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.6% were married couples living together, 17.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.3% were non-families. 28.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.08.

In 2000, age distribution was 26.5% under the age of 18, 11.1% from 18 to 24, 23.6% from 25 to 44, 18.3% from 45 to 64, and 20.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.2 males.

In 2000, the median household income was $23,576, and the median family income was $27,617. Males had a median income of $21,890 versus $18,678 for females. The per capita income for the city was $11,897. About 21.3% of families and 27.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 40.4% of those under age 18 and 13.4% of those age 65 or over.

Government

[edit]Avon Park operates under a council-manager form of government, with a city manager who operates under the direction of an elected four-member council and mayor. The current mayor is Garrett Anderson, and the City Manager is Danielle M. Kelly.[30] The city provides fire protection, utilities, and sanitation service to its residents. Highlands County Sheriffs provide law enforcement.

Transportation

[edit]Avon Park Executive Airport is a public-use airport located 2 miles (3.2 km) west of the central business district.

Education

[edit]Public schools

[edit]- Avon Elementary School

- Park Elementary School

- Memorial Elementary School

- Avon Park Middle School

- Avon Park High School

Private schools

[edit]- Walker Memorial Academy

- Central Florida Academy

- Parkview Pre-K LLC

- Community Christian Academy

- Cornerstone Christian Academy

Colleges

[edit]Media

[edit]Television

[edit]Avon Park is located in a fringe viewing area; its television stations originate in distant cities. Local television services offer signals from WFTV, the ABC affiliate in Orlando; WINK-TV, the CBS affiliate in Fort Myers/Naples; WFLA-TV, the Tampa Bay area NBC affiliate; and WTVT, the Tampa Bay area Fox affiliate.

Radio

[edit]Avon Park is in the Sebring radio market, which is ranked as the 288th largest in the United States by Arbitron.[31] Radio stations broadcasting from Avon Park include WAVP/1390 (Adult Hits), WAPQ-LP/95.9 (Religious), WWOJ/99.1 (Country) "OJ99.1" & WWMA-LP/107.9 (Religious).

Newspapers

[edit]Local print media includes the News-Sun, a newspaper published on Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday. Highlands Today, a daily local supplement to The Tampa Tribune that covered events in Highlands County, was bought by and merged into The Highlands News Sun in 2016.

Points of interest

[edit]

- Avon Park Air Force Range

- Avon Park Historic District

- Lake Adelaide

- Lake Isis

- Lake Tulane

- Lake Verona

Notable people

[edit]- David A. Brodie (1867–1951) – agriculturist and college football coach

- Red Causey (1893–1960) – Major League Baseball (MLB) player

- Eric Cheape (1885–1973) – college football player

- Rickey Claitt (b. 1957) – National Football League (NFL) player

- Derrick Crawford (b. 1979) – NFL player

- Shelby Dressel (b. 1990) – country singer-songwriter

- Nick Gordon (b. 1995) – MLB player

- Tom Gordon (b. 1967) – MLB player and sports commentator

- Ben H. Griffin Jr. (1910–1990) – businessman, philanthropist, and Florida state politician

- Dee Hart (b. 1992) – NFL player

- Hal McRae (b. 1945) – MLB player and manager

- Conrad H. Moehlman (1879–1961) – Baptist author and emeritus professor of church history

- Bernice Mosby (b. 1984) – Women's National Basketball Association and Women's Korean Basketball League basketball player

- Deanie Parrish (1922–2022) – U.S. Army Air Force aviator for WASP during World War II

- Charles K. Pringle (1931–2024) – Mississippi state politician

- Howard E. Skipper (1915–2006) – Chemical Corps researcher and oncologist

- Cecil Souders (1921–2021) – NFL player

- Dee Strange-Gordon (b. 1988) – MLB player

- Ernie Steury (1930–2002) – physician and Christian missionary

- Leslie Wolfsberger (b. 1959) – Olympic gymnast

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "Avon Park, United States Page". Falling Rain Genomics. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Avon Park city, Florida". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 28, 2017.[dead link]

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ Kevin M. McCarthy, African American Sites in Florida, p. 95

- ^ Byrne, Jason (April 27, 2023). "Cardinals Played in Avon Park from 1927-1929". Florida History Blog. Retrieved November 8, 2024.

- ^ "The Roar of the 20s in Two Centuries". Florida Grapefruit League. Retrieved November 8, 2024.

- ^ Byrne, Jason (August 28, 2022). "Avon Park City Council Throws Out All Black Votes in 1951 Election". Florida History Blog. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ "Gough v. State". Casetext. November 20, 1951. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ "Supreme Court Halts Action In Contested Avon Park Vote". The Tampa Tribune. October 10, 1951. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ "USAF ACCIDENT REPORT SUMMARY SHEET". Aviation Archaeology.

- ^ "Accident Republic F-84E Thunderjet 49-2070, Saturday 4 November 1950".

- ^ "MacDill Crash All Victims Here". Tampa Times. March 22, 1958. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ "Summary of Major Events and Problems: (Reports Control Syrnbol CSHIS-6) United States Army Chemical Corps, Fiscal Year 1959". United States Army Chemical Corps. pp. 101–104. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ Gilmore, Daniel F. (October 29, 1980). "Swarms of mosquitoes, the type notorious for transmitting yellow fever, were released in Georgia and Florida in the 1950s by the Army to see if the insects could be used as biological warfare weapons, documents show". United Press International. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ "Avon Park Ordinance 08-06" (PDF). City of Avon Park. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ Sanchez, Christina E. (July 26, 2006). "Avon Park mayor isn't giving up". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Hutchinson, Bill (August 5, 2006). "Avon Park's debate far from finished". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, TIGERweb, accessed April 28, 2017

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Avon Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Avon Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Avon Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Avon Park city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "City of Avon Park - City Manager". Avonpark.city. Archived from the original on January 2, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "Ratings–Sebring Market". Arbitron. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved August 16, 2007.