Prince Albert National Park

| Prince Albert National Park | |

|---|---|

| Parc national de Prince Albert | |

Lake Waskesiu in Prince Albert National Park | |

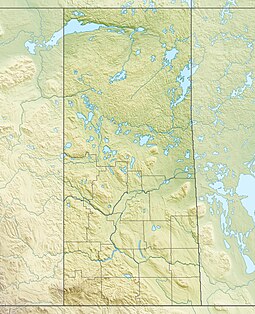

| Location | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Nearest city | Prince Albert |

| Coordinates | 53°57′48″N 106°22′12″W / 53.96333°N 106.37000°W |

| Area | 3,874 km2 (1,496 sq mi) |

| Established | March 24, 1927 |

| Visitors | 287,372 (in 2022–23[1]) |

| Governing body | Parks Canada |

| |

Prince Albert National Park encompasses 3,874 square kilometres (1,496 sq mi) in central Saskatchewan, Canada and is about 200 kilometres (120 mi) north of Saskatoon. Though declared a national park March 24, 1927, official opening ceremonies weren't performed by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King until August 10, 1928.[2] This park is open all year but the most visited period is from May to September. Although named for the city of Prince Albert, the park's main entrance is actually 80 kilometres (50 mi) north of that city via Highways 2 and 263, which enters the park at its southeast corner. Two additional secondary highways enter the park, Highway 264, which branches off Highway 2 just east of the Waskesiu townsite, and Highway 240, which enters the park from the south and links with 263 just outside the entry fee-collection gates. Prince Albert National Park is not located within any rural municipality, and is politically separate from the adjacent Northern Saskatchewan Administration District (NSAD). Until the establishment of Grasslands National Park in 1981, it was the province's only national park.

The hamlet of Waskesiu Lake is the only community within the park and it is located on the southern shore of Waskesiu Lake. Most facilities and services one would expect to find in a multi-use park are available there, such as shopping, fuel, and lodging.

About 90% of the park is in the Waskesiu Hills and elevations range from 488 metres (1,601 ft) on the western side to 724 metres (2,375 ft) on the eastern side.[3] There are several large lakes in the park, including Waskesiu, Kingsmere, and Crean, and several notable rivers have their source there, such as Spruce, Sturgeon, and Smoothstone.

The park's development as a recreation destination has led to the region immediately south-east of the park boundaries – locations such as Christopher Lake, Emma Lake, Sunnyside Beach, and Anglin Lake, themselves becoming popular recreation destinations. Additional development has taken place just beyond the park's eastern entry.

Biology

[edit]

Prince Albert National Park represents the southern boreal forest region of Canada. It is a rolling, mostly forested landscape that takes in the drainage divide between the North Saskatchewan and Churchill Rivers. The boreal forest extends northerly into the Canadian Shield area from the agricultural zones of southern Canada. Prince Albert National Park lies south of the Shield in landscapes that were shaped by Pleistocene glaciers that deposited glacial till, sand and other materials that were later colonized by trees and shrubs.[4]

Most of the park is dominated by coniferous forests, with the cover of jack pine and white spruce becoming more prevalent the farther north one goes. The very southern part of the park is predominantly aspen forest with an understorey of elderberry, honeysuckle, rose, and other shrubs and openings and meadows of fescue grassland. The fescue grasslands are considered ecologically important because of their rarity; outside the park, most of the native fescue grasslands have been lost to the plough or to urban development.

Wildlife

[edit]Some of the many animals are elk, moose, red foxes, beavers, white-tailed deer, badgers, river otters, red squirrels, black bears, coyotes, and timber wolves. The aspen forest/meadow mosaic in the south-west corner of the park is particularly unique as it sustains a growing herd of more than 400 plains bison, the only free-ranging herd in its original range in Canada that has a full array of native predators, including timber wolves.[5] Boreal woodland caribou from a regional population that is declining due to loss of habitat to forest logging range sometimes into the park, but their core habitat lies outside the park to the north. White-tailed deer, elk, and moose are the common ungulates.[4] Flycatchers, Tennessee warblers, double-crested cormorants, red-necked grebes, brown creepers, nuthatches, three-toed woodpeckers, bald eagles, osprey, great blue herons, many species of ducks, and the common loon are just a few of the water fowl and birds which make their home in the park. There are 21 species of fish recorded in the park, including Iowa darter, yellow perch, brook stickleback, spottail shiner, cisco, northern pike (locally called "jack fish"), walleye (locally called "pickerel"), and lake trout.[4] Although most people visit the park in summer, the best wildlife watching is often in the winter.

The park is noted for its numerous lakes including three very large lakes — Waskesiu, Kingsmere, and Crean. The water quality is high and fish populations robust, except for lake trout that were commercially fished to near-extinction in Crean Lake in the early 20th century and, in spite of protection, have yet to recover their former numbers. Northern pike, walleye, suckers, and lake whitefish are among the most common larger fish. One of Canada's largest white pelican colonies nests in an area closed to public use on Lavallée Lake in the north-west corner of the park, and pelicans, loons, mergansers, ospreys, and bald eagles are common in summer. Otters are seen regularly, year round. Winter is an especially good time to find otters as they spend considerable time around patches of open water on the Waskesiu Lake Narrows and the Kingsmere and Waskesiu Rivers.

History

[edit]

There are archeological traces of pre-history in the park reserve in the form of tools which have been located.

- Early Pre-contact (11,000 to 7500 BP)

- Middle Pre-contact (7500 to 2000 BP)

- Late Pre-contact (2000 to 200 BP)

- Post Contact or Historic (200 BP to Present)

At Waskesiu Lake, there was an early Hudson's Bay Company fur trading post between 1886 and 1893.

In 1908–1909 the New Northwest expeditions led by Frank Crean were the first to document the region, with the extensive use of photography and the mapping of lakes. Crean Lake was named in honour of Frank.

In the early 20th century the industries of fishing and logging were carried out in this boreal forested area. The large 1919 forest fire eliminated the logging industry.[6]

Indigenous peoples who traditionally lived on the lands were forcibly removed from the land by federal officials and the RCMP upon creation of the park in 1927, with their possessions and cabins destroyed.[7][8]

The park was the subject of a short film in 2011's National Parks Project, directed by Stéphane Lafleur and scored by Andre Ethier, Mathieu Charbonneau, and Rebecca Foon.

Grey Owl

[edit]The Dominion Parks Service hired Grey Owl, Archibald Stanfield Belaney (September 18, 1888 – April 13, 1938), as the first naturalist. He lived on Ajawaan Lake in Prince Albert National Park and wrote of wilderness protection: Pilgrims of the Wild (1935), Sajo and the Beaver People (1935), and Empty Cabin (1936).[9] He was played by Pierce Brosnan in the 1999 feature film, Grey Owl.

Activities

[edit]There are many things to do in this park:

Scenic driving tours

[edit]There are a few main roads through the park.

- The Narrows Road along Waskesiu Lake's southern shore, with many points of interest and picnic areas, ending at a 200-metre narrows, where there is a campground.

- Lakeview Drive or Scenic Route #263 which provides access to several other lakes: Namekus, Trappers, Sandy (also called Halkett); as well as many trails.

- Highway 264 to Kingsmere River, which accesses a small boat or canoe launch site midway between Kingsmere and Waskesiu lakes, and a trail through a railway portage to Kingsmere Lake.

Picnicking

[edit]There are many picnic sites within the park, set up with picnic tables, scenic views, campfire pits and swimming areas.[10]

- Namekus Lake

- Sandy Lake

- South Gate

- Meridian Day

- South Bay

- Trippes Beach

- King Island

- Paignton Beach

- The Narrows

- Waskesiu River

- Waskesiu Landing (Main Marina)

- Point View

- Birch Bay

- Heart Lakes

- Kingsmere

Hiking

[edit]These trails are 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) in length or less. They each have descriptive guided brochures which help to identify the natural sights along the way.

- Boundary Bog Trail

- Mud Creek Trail

- Treebeard Trail

- Waskesiu River Trail

- Kingsmere River Trail

- Red Deer Trail (Red, Blue, and Yellow)

- Ice-Push Ridge Trail

- Narrows Peninsula Trail

- Spruce River Highlands Tower Trail

There are longer trails for the backpacker and hiker which vary from 13 kilometres in length and to 54 kilometres (return).

- Kingfisher Trail

- Grey Owl Trail

- Fish Trail

- Hunters Trail

- Spruce River Highlands Trail

Swimming

[edit]Surrounding Waskesiu Lake there are several beaches to take in swimming during the hot summer months. There are also good beaches at the south end of Kingsmere Lake (boat or trail access), Namekus Lake, and Sandy Lake.

Canoeing

[edit]Bagwa Canoe Route and Bladebone Canoe Route are two canoe routes of varying lengths. As well the park offers a multitude of lakes which are amenable to the canoe enthusiast. Amiskowan, Shady, Heart, Kingsmere, and Waskesiu lakes are just a few of them.[11]

Boating

[edit]Power boats are only permitted on some of Prince Albert National Park's lakes. Motor boats are allowed on Waskesiu, Crean, Kingsmere, Sandy, and the Hanging Heart Lakes. There is a limit of 40 horsepower motors on Kingsmere. The Waskesiu Marina, Heart Lakes Marina, and the Narrows have boat launches (permit and fee required) and docks. Boat, canoe, and kayak rentals are available at all three, by the hour or by the day. The Waskesiu Marina has a concrete breakwater and a permit is required to use boat launch facilities. Personal watercraft are not allowed on any lakes. Canoes, kayaks, and sail boats are allowed on all waters.

Fishing

[edit]Just like those who used the waters for commercial fishing in the early 20th century, campers may also find relaxation fishing for northern pike, walleye, lake trout, whitefish, or yellow perch. The park requires purchase of its own licences to fish in the park and limits and seasons are different from the province of Saskatchewan. Some areas, e.g., spawning grounds, are closed to fishing.[12]

Camping

[edit]At this park one can choose from serviced or unserviced 'front country' camping or go by canoe / boat and backpacking, and choose 'back country' camping. Most back country camping occurs on Kingsmere and Crean lakes. Permits and fees are required for all camping, whether front or back country. Front country sites can be reserved by website or telephone.[13]

Open fires are allowed at campsites (Excluding Red Deer Campground), after payment for a "fire permit" (fire permits are not required in picnic areas).

The following are accessible by automobile and can accommodate trailers and motorhomes:

- Beaver Glen Campground on the east margins of the Waskesiu town site has electricity to half of its 213 sites (no water or septic hook-ups), washrooms with hot and cold water and showers, central septic tank service, and drinking water. Sites can be booked in advance through the Parks Canada Campground Reservation Service through a toll free number or via online reservation. Details about how to reserve can be found at the Parks Canada website.

- Red Deer Campground, formerly "Trailer Court" is to the immediate South-West of Beaver Glen in the Waskesiu townsite. This site has power, water, and sewage hookups at each of its 161 pull through sites and is designed for large trailers and motorhomes. There are no open fires are allowed at Red Deer. Sites in Red Deer can be booked in advance in the same way as Beaver Glen.

- The Narrows Campground has flush toilet washrooms with cold water only, and no other services. Sites at the Narrows are first come, first served.

- Namekus Lake and Sandy Lake Campgrounds have septic tank toilets, water source (not drinkable without treatment). These sites are also first come, first served.

There are a series of boat-accessible campsites – the level of waves that can come up with overnight weather changes on Waskesiu, Kingsmere, and Crean lakes, provide some risk for boats that cannot be completely pulled out of the water at night.

Interpretive programs

[edit]The nature centre in the Waskesiu townsite has information about interpretive programs

- Freight Trail – 27 km one way

- Elk Trail – 39 km one way

- Fish Lake Trail – 12 km one way

- Hunters Lake Trail – 12 km one way

- Westside Boundary Trail – 37 km one way

- Red Deer Trail – three loops totalling 17 km

- Kinowa Trail – 5 km one way

- Amyot Lake Trail – 15.5 km loop

Bicycle rentals are available in Waskesiu townsite.

Wildlife and bird watching

[edit]Flycatchers, Tennessee warblers, red-necked grebe, brown creepers, nuthatches, three-toed woodpeckers, bald eagle, osprey, great blue herons, common loon are just a few of the many bird species to be seen in the park. Elk, black bear, fox, moose, beaver, deer, otter are a sampling of wild life of the park area.[14][15]

Although most people visit the park in summer, the best wildlife watching is often in the winter. Wolves often travel on the frozen lakes and along the ploughed roads, and elk and deer are common right in the town of Waskesiu. Open water at the Narrows on Waskesiu Lake and where the Waskesiu River exits from the lake makes otter sightings very reliable. Foxes, including the red, cross, and silver colour phases, are frequent sightings in winter too.

Golfing

[edit]Stanley Thompson designed an 18-hole golf course in the park. It was built in the early 1930s. Its official name is the Waskesiu Golf Course, but is often called "The Lobstick" after a tournament it hosts each year.[16]

Climate

[edit]Waskesiu experiences a borderline humid continental/subarctic climate (Köppen Dfb/Dfc). The highest temperature ever recorded in Waskesiu was 36.5 °C (98 °F) on June 5, 1988.[17] The coldest temperature ever recorded was −48.3 °C (−55 °F) on January 21, 1935.[17]

| Climate data for Waskesiu Lake, 1981−2010, extremes 1934–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

36.5 (97.7) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

31.7 (89.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

36.5 (97.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −11.7 (10.9) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

6.9 (44.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −16.5 (2.3) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

2.7 (36.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

2.9 (37.2) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −21.1 (−6.0) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−16.5 (2.3) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −48.3 (−54.9) |

−47.0 (−52.6) |

−40.0 (−40.0) |

−30.0 (−22.0) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−35.0 (−31.0) |

−42.2 (−44.0) |

−48.3 (−54.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 15.6 (0.61) |

16.0 (0.63) |

21.7 (0.85) |

27.0 (1.06) |

46.9 (1.85) |

71.3 (2.81) |

86.1 (3.39) |

64.7 (2.55) |

57.9 (2.28) |

31.3 (1.23) |

19.0 (0.75) |

22.2 (0.87) |

479.7 (18.89) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.02 (0.00) |

0.3 (0.01) |

5.5 (0.22) |

18.5 (0.73) |

45.6 (1.80) |

71.3 (2.81) |

86.1 (3.39) |

64.7 (2.55) |

57.5 (2.26) |

22.5 (0.89) |

3.5 (0.14) |

0.0 (0.0) |

375.4 (14.78) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 13.5 (5.3) |

17.1 (6.7) |

15.6 (6.1) |

8.5 (3.3) |

1.3 (0.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.2) |

8.8 (3.5) |

15.6 (6.1) |

23.5 (9.3) |

104.2 (41.0) |

| Source: Environment Canada[17][18][19] | |||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- List of National Parks of Canada

- List of protected areas of Saskatchewan

- Tourism in Saskatchewan

- Royal eponyms in Canada

References

[edit]- ^ Canada, Parks. "Parks Canada attendance 2022_23 - Parks Canada attendance 2022_23 - Open Government Portal". open.canada.ca. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park of Canada – Park Era History". Parks Canada. August 10, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan | Details".

- ^ a b c "Teacher Resource Centre – Prince Albert National Park of Canada". Parks Canada. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ Piller, Thomas (April 12, 2021). "Sturgeon River bison herd almost double from record low: ecologist". Global News. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park of Canada – Pre-Park Area History". Parks Canada. August 14, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ Warick, Jason (September 22, 2018). "'All we can do is forgive': Descendants of Métis trapper visit site of his eviction by federal government". CBC News. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Harold R. (2019). Peace and Good Order: The Case for Indigenous Justice in Canada. McClelland & Stewart. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7710-4872-2.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park of Canada – Grey Owl". Parks Canada. August 14, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park of Canada – Picnicking & Day Use". Parks Canada. February 8, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park of Canada – Canoeing". Parks Canada. February 8, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park of Canada – Fishing". Parks Canada. February 8, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park of Canada – Campground Reservations". Parks Canada. January 25, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park of Canada – Cycling". Parks Canada. February 8, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Prince Albert National Park". Virtual Saskatchewan. 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ "Course History". Waskesiu Golf Club. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Waskesiu Lake". Environment Canada. June 22, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "Waskesiu Lake". Environment Canada. June 22, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "Waskesiu Lake". Environment Canada. June 22, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Prince Albert National Park at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prince Albert National Park at Wikimedia Commons