Alparslan Türkeş

Alparslan Türkeş | |

|---|---|

| |

| Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey | |

| In office 21 July 1977 – 5 January 1978 | |

| Prime Minister | Süleyman Demirel |

| Served with | Necmettin Erbakan |

| Preceded by | Orhan Eyüboğlu |

| Succeeded by | Turhan Feyzioğlu |

| In office 31 March 1975 – 21 June 1977 | |

| Prime Minister | Süleyman Demirel |

| Served with | Necmettin Erbakan Turhan Feyzioğlu |

| Preceded by | Zeyyat Baykara |

| Succeeded by | Orhan Eyüboğlu |

| Leader of the Nationalist Movement Party | |

| In office 8 February 1969 – 4 April 1997 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Devlet Bahçeli |

| Member of the Grand National Assembly | |

| In office 10 October 1991 – 24 December 1995 | |

| Constituency | Yozgat (1991) |

| In office 10 October 1965 – 12 September 1980 | |

| Constituency | Ankara (1965) Adana (1969, 1973, 1977) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hüseyin Feyzullah[1] 25 November 1917 Nicosia, British Cyprus |

| Died | 4 April 1997 (aged 79) Ankara, Turkey |

| Political party | CKMP (1965–1969) MHP (1969–1980), (1993-1997) MÇP (1987–1993) |

| Spouses | Muzaffer Hanım

(m. 1940; died 1974)Seval Hanım (m. 1976) |

| Children | 7, including Tuğrul, Ahmet and Ayyüce |

| Alma mater | Kuleli Military High School |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Turkey |

| Branch/service | Turkish Army |

| Years of service | 1933–1963 |

| Rank | Colonel |

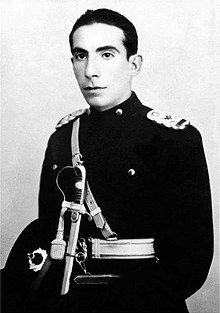

Alparslan Türkeş[a] (Turkish pronunciation: [alˈpaɾsɫan tyɾˈceʃ]; 25 November 1917 – 4 April 1997) was a Turkish politician, who was the founder and president of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and the Grey Wolves (Ülkü Ocakları). He ran the Grey Wolves training camps from 1968 to 1978. More than 600 people are said to have fallen victim of political murders by the Grey Wolves between 1968 and 1980.[5] He represented the far-right of the Turkish political spectrum. He was and still is called Başbuğ ("Leader") by his devotees.[6]

Early life

[edit]Türkeş was born in Nicosia, British Cyprus, to a Turkish Cypriot family in 1917.[7][8][9] His birth name is disputed, some claiming that it is Hüseyin Feyzullah,[10] while MHP claims it is Ali Arslan.[11] His paternal great-grandfather had emigrated to Cyprus from Kayseri, Central Anatolia, Ottoman Empire, in the 1860s.[12] His father, Ahmet Hamdi Bey, was from Tuzla, near Famagusta, and his mother, Fatma Zehra Hanım, was from Larnaca.[13] However, in an interview with the scholar Fatma Müge Göçek the journalist Hrant Dink claimed that Türkeş was of Armenian descent, an orphan originally from Sivas who was later adopted by a Muslim couple from Cyprus.[14] In 1932, with fifteen years of age, Türkeş emigrated to Istanbul, Turkey with his family.[15] He was enrolled into the military lycée in Istanbul in 1933 and completed his secondary education in 1936.[12] In 1938, he joined the army and his military career began.

Racism-Turanism trials

[edit]Along with other nationalists like Nihal Atsız and Nejdet Sançar,[16] Türkeş was court-martialed on charges of "fascist and racist activities" in 1945.[17] He spent 10 months in prison before he was released the same year. The charges were eventually dismissed in 1947.[16] The trial would become known as the Racism-Turanism trials.[18]

Political career

[edit]He attained fame as the spokesman of the 27 May 1960 coup d'état against the government of Prime Minister Adnan Menderes, who was later executed after the Yassiada trial. He assumed a position as an undersecretary of the Prime Minister.[19] However Türkeş, together with 13 other members of the junta, declared their opposition to returning the power back to civilians and therefor were expelled by an internal coup within the junta (National Unity Committee).[20] Türkeş was sent into exile to the Turkish embassy in New Delhi.[21] He returned in February 1963[22] and together with others of the fourteen, he later joined the Republican Villager Nation Party (Turkish: Cumhuriyetçi Köylü Millet Partisi, CKMP).[23] Türkeş was elected as its chairman on 1 August 1965.[24] In 1969 the CKMP was renamed the Nationalist Movement Party (Turkish: Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP).[25] As leader of the MHP he was also the de facto leader of the Grey Wolves. This far-right movement executed political murders, which began in 1968. More than 600 people are said to have fallen victim between 1968 and 1980.[5]

Türkeş served as Deputy Prime Minister in right-wing National Front (Turkish: Milliyetçi Cephe) cabinets in the 1970s.[26] After the Military coup of 1980, he was imprisoned for more than four years and the Government demanded the death sentence for him as well as other Turkish nationalists. But in a turn of events he was released on 9 April 1985.[16] He rejoined the political arena within the Nationalist Workers Party (MÇP) in 1987[16] and was elected to parliament representing the province of Yozgat on a ticket of the Welfare Party (RP) in 1991.[27] In 1992 the name Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) was relaunched in exchange of the name of the MÇP and the party logo of the three crescents was presented to the public.[16]

Ideology

[edit]Through the far-right MHP, Türkeş took the rightist views of his predecessors like Nihal Atsız, and transformed them into a powerful political force. In 1965, Türkeş released a political pamphlet titled Nine Lights Doctrine (Turkish: 9 Işık Doktrini), which formed the basis of the nationalist ideology of the CKMP.[28] This text listed nine basic principles which were: nationalism; idealism; moralism; scientism; societalism; ruralism; libertism and personalism; progressivism and populism; industrialism and technologism.[29]

Hans-Lukas Kieser notes that although Türkeş openly identified with pan-Turkism and sympathised with National Socialism as well as Adolf Hitler, he was still allowed to rise through the ranks of the Turkish Army and was even allowed to move to the United States in order to pursue military education and cooperation within NATO.[30] Türkeş led the vanguard of anti-communism in Turkey; he was a founding member of the Counter-Guerrilla, the Turkish Gladio.[21]

He has been the spiritual leader of the Idealism Schools Foundation of Culture and Art (Turkish: Ülkü Ocakları Kültür ve Sanat Vakfı). His followers consider him to be one of the leading icons of the Turkish nationalist movement.

International politics

[edit]The wellbeing of the greater Turkish nation living in a so-called Turan, which according to him included Turks wherever they lived, be it in Greece, Cyprus or elsewhere, was key concern of his political views.[31] On 28 April 1978 he was received by Franz Josef Strauss, former minister for defense and finance in Germany and acting president of the CSU party.[32][33] In 1992, Alparslan Türkeş visited Baku to support Abulfaz Elchibey during the Azerbaijan presidential election. He also had a meeting with Levon Ter-Petrosyan, the President of Armenia in the 1990s.[34]

Personal life

[edit]Türkeş was married twice and had seven children.[35] He married Muzaffer Hanım in 1940 and had four daughters (Ayzit, Umay, Selcen and Çağrı) and one son (Tuğrul) with her. Their marriage lasted until his wife's death in 1974. By 1976 Türkeş married Seval Hanım and had one daughter (Ayyüce) and one son (Ahmet Kutalmış).[36]

Türkeş died of a heart attack at the age of 80 on 4 April 1997.[35][37] The announcement of his death was delayed for five hours while nationwide security measures were implemented; thereafter, thousands of his supporters went to the Bayindir Hospital chanting "Leaders never die".[38] His funeral was held in Kocatepe Mosque in Ankara.[38]

Türkeş's youngest son, Ahmet Kutalmış Türkeş, is a member of the Justice and Development Party and was elected as an Istanbul deputy in 2011. However, he resigned several days before the June 2015 elections, protesting the party's plans to transform the parliamentary system into a presidential one.[39][40]

In 2015, Türkeş's eldest son, Tuğrul Türkeş, became the first person of Turkish Cypriot origin to be Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey.[41] In September 2015, Türkeş made his first official visit to Northern Cyprus.[42] As an independent parliamentarian, Türkeş has criticized the Nationalist Movement Party (founded by his father) and the Republican People's Party for their unwillingness to compromise, which led to the November 2015 elections.[43]

Legacy

[edit]

Türkeş was a key figure in shaping Turkish nationalism and reviving Pan-Turkism from the 1940s onwards. Soon after his death in 1997, Turkish President Süleyman Demirel stated that his passing had been a "great loss to the political life of Turkey". Similarly, Turkey's first female Prime Minister Tansu Çiller described him as a "historic individual".[38]

Controversies

[edit]When he died, it was revealed that he had embezzled 2 trillion lira from the European Turkish Federation. The pan-Turkist group had created a secret slush fund to support the Second Chechen War and help Abulfaz Elchibey succeed in Azerbaijan.[44] The money was formerly administered by Enver Altaylı, who had been part of the Azerbaijan coup plot. His daughters, Ayzıt and Umay Günay, quarreled over who was the rightful owner despite the fact that it was neither of them.[45] The two appeared before the Ankara 7th High Penal Court for fraud. The indictment said that Türkeş' account in a U.K. branch of the Deutsche Bank held 575,000 DM, US$845,000, and 367,000 GBP.[46] The court concluded that Ayzıt had withdrawn 200,000 GBP while Umay Günay had withdrawn 42,000 GBP.[47] Ayzıt said that she had been living in the UK since 1975, and that her father opened the account in 1988, giving her complete access to it. She said that her father had instructed her to fulfill his financial obligations in support of "the cause of Turkishness" upon his death by making certain payments.[48] Türkeş' second wife, Seval, refuted Ayzıt's claim that she had not kept the money to herself. Seval claims that she and her sons' Ayyüce and Ahmet Kutalmış share of the withdrawn 242,000 GBP is 112,355 GBP.[47]

The MHP's chairman, Devlet Bahçeli, instructed his deputies to keep mum, fearing that the scandal could lead to the dissolution of the party.[49]

The case was closed due to the statute of limitations.[50]

Works

[edit]- Ülkücülük; Hamle Yayınevi; İstanbul, 1995.

- 12 Eylül Adaleti (!) : Savunma; Hamle Yayınevi; İstanbul, 1994.

- 1944 Milliyetçilik Olayı; Hamle Yayınevi;

- Türkeş'li Yıllar; Hasan Sami BOLAK

- Modern Türkiye; İstanbul.

- Milliyetçilik Olayları; Berikan Elektronik Basım Yayım.

- 27 Mayıs ve Gerçekler; Berikan Elektronik Basım Yayım.

- 27 Mayıs, 13 Kasım, 21 Mayıs ve Gerçekler; İstanbul, 1996.

- Ahlakçılık; Berikan Elektronik Basım Yayım.

- Etik (Ahlak Felsefesi), Etik.; Bunalımdan Çıkış Yolu; Kamer Yayınları.

- Türk Edebiyatında Anılar, İncelemeler, Tenkidler, Anı-Günce-Mektup; İstanbul, 1994.

- Bunalımdan Çıkış Yolu; Hamle Yayınevi; İstanbul, 1996.

- Dış Meselemiz; Berikan Elektronik Basım Yayım.

- İlimcilik; Berikan Elektronik Basım Yayım.

- Kahramanlık Ruhu; İstanbul, 1996.

- Temel Görüşler; Kamer Yayınları.

- Sistemler ve Öğretiler; İstanbul, 1994.

- Türkiye'nin Meseleleri; Hamle Yayınevi; İstanbul, 1996.

- Yeni Ufuklara Doğru; Kamer Yayınları.

- Sistemler ve Öğretiler; İstanbul, 1995

Notes

[edit]- ^ His name was a nom de guerre he took as an official name after 1934. His former name is a subject of debate. His official biography cites Ali Arslan,[2] while other sources claim Hüseyin Feyzullah.[3][4] His close friends and old acquaintances called him Albay ("Colonel").[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ De Tapia, Stephane (2011). Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus: eine Beziehungs- und Konfliktgeschichte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 304. ISBN 9783525369227.

- ^ "BAŞBUĞ Alparslan TÜRKEŞ". Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ Muradoğlu, Abdullah (16 August 2003). "Türkeş'in Gizli Dünyası". Yeni Şafak (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- ^ Cevik, Ilnur (11 April 1997). "Turkish Nationalists Lose Their Leader". Turkish Daily News. Hürriyet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Auslandsbezogener Extremismus". BundesamtfuerVerfassungsschutz (in German). 1 September 2023. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Başbuğ Alparslan Türkeş'i Anma Etkinlikleri (in Turkish)

- ^ Zürcher, Erik J. (2004). Turkey: A Modern History. I.B.Tauris. p. 404. ISBN 1860649580.

- ^ Bacik, Gokhan (2010). "The Nationalist Action Party: The Transformation of the Transnational Right in Turkey". In Durham, Martin (ed.). New Perspectives on the Transnational Right. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 110. ISBN 978-0230115521.

- ^ Uzer, Umut (2004). Identity and Turkish Foreign Policy: The Kemalist Influence in Cyprus and the Caucasus. I.B.Tauris. p. 37. ISBN 0857719017.

- ^ De Tapia, Stephane (2011). Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus: eine Beziehungs- und Konfliktgeschichte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 304. ISBN 9783525369227.

- ^ "Türk Dünyasının Bilge Lideri Türk Milliyetçiliğinin Kurucusu Başbuğ Alparslan TÜRKEŞ'in Hayatı".

- ^ a b Landau, Jacob M. (2004). Exploring Ottoman and Turkish History. C. Hurst & Co. p. 190. ISBN 1850657521.

- ^ Tekin, Arslan (2009). Alparslan Türkeş ve Liderlik. Bilgeoğuz. p. 71. ISBN 978-6055965808.

- ^ Göçek, Fatma Müge. The Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present, and Collective Violence against the Armenians, 1789-2009. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 598, note 71.

- ^ Landau, Jacob M. (1974). Radical Politics in Modern Turkey. Brill publishers. p. 206. ISBN 978-90-04-04016-8.

- ^ a b c d e "PROFILE – Turkish nationalist leader commemorated 23 years on". aa.com.tr. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Özkırımlı, Umut and Spyros A. Sofos, Tormented by history, (Columbia University Press, 2008), 138.

- ^ Aytürk, İlker (April 2011). "The Racist Critics of Atatürk and Kemalism, from the 1930s to the 1960s". Journal of Contemporary History. 46 (2): 308–335. doi:10.1177/0022009410392411. hdl:11693/21963. ISSN 0022-0094. S2CID 159678425.

- ^ Aytürk, İlker (8 November 2017). "The Flagship Institution of Cold War Turcology". European Journal of Turkish Studies. Social Sciences on Contemporary Turkey (24). doi:10.4000/ejts.5517. ISSN 1773-0546.

- ^ Kerslake, Celia (25 February 2010). Turkey's Engagement with Modernity: Conflict and Change in the Twentieth Century. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 97. ISBN 9780230277397.

- ^ a b Lucy Komisar, Turkey's terrorists: a CIA legacy lives on, The Progressive, April 1997

- ^ Landau, Jacob M. (1974). Radical Politics in Modern Turkey. E.J. Brill. p. 207.

- ^ Landau, Jacob M. (1974). Radical Politics in Modern Turkey. E.J. Brill. p. 208.

- ^ Landau, Jacob M. (1974). Radical Politics in Modern Turkey. E.J. Brill. p. 209.

- ^ Ümit Hassan, Halil Berktay, Türkiye tarihi: Çağdaş Türkiye, 1908–1980, Cilt 4, Cem Yayınevi, 1987, p. 224.

- ^ Barış Yetkin, Kırılma Noktası / 1 Mayıs 1977 Olayı, Yeniden Anadolu ve Rumeli Müdafaa-i Hukuk Yayınları, 2000, ISBN 978-9944-5966-8-8, p. 19.

- ^ Şafak, Yeni (28 May 2020). "Yozgat Seçim Sonuçları 1991 – Genel Seçim 1991". Yeni Şafak (in Turkish). Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Landau, Jacob M. (1981). Pan Turkism in Turkey, study of irredentism. C. Hurst & Co. p. 150. ISBN 0905838572.

- ^ Alparslan Türkeş, Millî Doktrin Dokuz Işık, Genişletilmiş Birinci Baskı, Hamle Basın Yayın., İstanbul, s. 15.

- ^ Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2021). "Europe's Seminal Proto-Fascist? Historically Approaching Ziya Gökalp, Mentor of Turkish Nationalism". Die Welt des Islams. 61 (4): 413 (note 5). doi:10.1163/15700607-61020008. S2CID 241148959.

- ^ Landau, Jacob M. (1981), pp.150–151

- ^ "Dann kommt alles ins Rollen". Der Spiegel. 24 February 1980.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Çamlıbel, Cansu (27 December 2013). "Calling 1915 inhumane helps Turkey, Armenia". Hurriyet.

- ^ a b de Bellaigue, Christopher (22 October 2011). "Obituary: Alpaslan Turkes". The Independent. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "MHP hakkını aramadı". Sabah. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Alpaslan Turkes, Turkish Rightist, 80". The New York Times. 10 April 1997. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "Turkes dead, all eyes on his legacy". Hurriyet Daily News. 4 June 1997. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "AK Party deputy resigns in protest of presidential system plans". Today's Zaman. Retrieved 30 October 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "AKP deputy resigns over 'divisive' presidential system concerns". Hurriyet Daily News. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Tuğrul Türkeş: Bu Türkiye'de ilk kez". Cumhuriyet. 21 September 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Türkeş visited TRNC". BRT. Retrieved 30 October 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Deputy PM Türkeş: MHP becoming single-man party with Bahçeli". Daily Sabah. 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "MHP accuses Turkes daughters of embezzlement". Turkish Daily News. Hürriyet. 13 February 2001. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ Sevinc, Şaban (12 February 2001). "Zimmete geçirdiler". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ "AYZIT TÜRKEŞ: Babam, 'Kızım kimse parayı bilmesin' dedi". Milliyet. 22 June 2001. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ a b "Türkeş'in çocukları miras için davalık". Sabah (in Turkish). 22 April 2007. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ "Ayzıt Türkeş: Vicdanım rahat". Güncel. Aksam (in Turkish). 22 June 2001. Archived from the original on 9 February 2005. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ Tahincioglu, Gokcer (13 February 2001). "Ayzıt'ın 'Hayır' işleri 'Türklük davası'ymış". Milliyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ "Zamanaşımına uğramıştı". Sabah (in Turkish). 22 April 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

External links

[edit]- Can Dündar (15 April 1997). "Başbuğ Türkeş". 40 Dakika. Archived from the original (WMV) on 15 March 2009.

- 1917 births

- 1997 deaths

- Cypriot emigrants to Turkey

- People from Pınarbaşı, Kayseri

- People from Kayseri Province

- Turkish colonels

- Kuleli Military High School alumni

- Turkish Military Academy alumni

- Army War College (Turkey) alumni

- Leaders of political parties in Turkey

- Turkish anti-communists

- Far-right politics in Turkey

- Deputy prime ministers of Turkey

- Turanists

- Idealism (Turkey)

- Alparslan Türkeş

- Turkish nationalists

- Nationalist Movement Party politicians

- Pan-Turkists

- Deputies of Ankara

- Turkish Cypriot politicians

- Deputies of Yozgat

- Members of the 39th government of Turkey

- Deputies of Adana

- Members of the 41st government of Turkey

- Republican Villagers Nation Party politicians

- People from Kayseri

- 20th-century Turkish politicians

- Turkish exiles

- Turkish political party founders

- People convicted in the Racism-Turanism trials

- Grey Wolves (organization)

- Grey Wolves (organization) members

- Turkish revolutionaries